AND IT WAS GOOD: Reflections on 20th Century American Choral Music in a 21st Century World

There is little doubt that the advance of technology, international communications, and access to educational opportunity has changed the complexion of musical composition during the 21st Century. There is much beautiful music being written these days. Maybe too much. And boundaries, styles and trends have been blurred more than ever before. None of this is surprising, given our 21st Century world, and it will be interesting to see what the world's 22nd Century population surmises as they reflect on the current musical landscape. As an Englishman, born in the late 1960s, my first exposure to American Choral Music was, predictably enough, hearing Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms performed at London’s Royal Festival Hall in 1973. For the decade or so after that, I was basically unaware of American Choral Music, as I became steeped in the Anglican Choral Tradition.

By Nicholas White

PROGRAM

Randall Thompson (1899-1984) - Alleluia

Aaron Copland (1900-1990) - In the Beginning

Samuel Barber (1910-1981) - Reincarnations

Mary Hynes

Anthony O’Daly

The Coolin

Stephen Paulus (1949-2014) - Two Pieces

Little Elegy

The Road Home

Morten Lauridsen (b. 1943) - Nocturnes

Sa Nuit d’Ete

Soneto de la Noche

Sure On This Shining Night

Randall Thompson - Farewell

There is little doubt that the advance of technology, international communications, and access to educational opportunity has changed the complexion of musical composition during the 21st Century. There is much beautiful music being written these days. Maybe too much. And boundaries, styles and trends have been blurred more than ever before. None of this is surprising, given our 21st Century world, and it will be interesting to see what the world's 22nd Century population surmises as they reflect on the current musical landscape. As an Englishman, born in the late 1960s, my first exposure to American Choral Music was, predictably enough, hearing Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms performed at London’s Royal Festival Hall in 1973. For the decade or so after that, I was basically unaware of American Choral Music, as I became steeped in the Anglican Choral Tradition.

The next piece of American Choral Music to which I was exposed was Randall Thompson’s Alleluia. I learned of this piece while undertaking a choir tour to the USA in 1988. My first tour of the States had happened the previous year, and the program was made up entirely of British – or, at least, European – choral music. Indeed, I think it is fair to say that there was a market for British choirs traveling to America in the 1980s and 1990s that was different to the situation we find today. Yes, elements of Anglican Choral Style have become more and more influential upon the way in which choirs function in our churches and concert halls over here. Equally though, there was a wall of ignorance and naïveté surrounding American Choral Music – even acknowledging its existence – that has now been broken down. Knowledge of, and appreciation for, international musical styles has increased exponentially over the last twenty years. The very best American choirs rival the very best European choirs, and compositions for these ensembles are able to traverse boundaries that are significantly changed since the last century.

In designing this program, I was intentional about featuring music that comes from the 20th Century, versus the 21st Century. While some of this music was penned after 2000, the foundation of the style is from an earlier time. Randall Thompson’s Alleluia was commissioned by Serge Koussevitsky in 1940 for the opening of the new Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood. Surprisingly subdued as a “fanfare”, Thompson once wrote that…

…the Alleluia is a very sad piece. The word "Alleluia" has so many possible interpretations. The music in my particular Alleluia cannot be made to sound joyous. It is a slow, sad piece, and...here it is comparable to the Book of Job, where it is written, "The Lord gave and the Lord has taken away. Blessed be the name of the Lord.”

I first heard Aaron Copland’s In The Beginning when I moved to Abilene, Texas in 1992. The excellent choir at Hardin-Simmons University, under the direction of Dr. Loyd Hawthorne, was preparing the piece for a contest. This substantial, polytonal piece, with its dramatic role for mezzo-soprano was composed for Harvard University's Symposium on Music Criticism in May 1947. The premiere was performed by the Collegiate Chorale at the Harvard Memorial Church, Cambridge on 2nd May, almost exactly seventy years ago, conducted by Robert Shaw.

As a teenager, Samuel Barber had developed an appreciation for his Irish heritage, had discovered the poetry of James Stephens, and had set one of Stephens’ poems as an art song. Barber set three poems, based on verse by the Gaelic poet Antoine O Reachtabhra (1784-1835), in what became his Reincarnations, one of his best-known choral works. He worked on the pieces separately in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The first performance of all three pieces as a single work was given at the Juilliard School in the summer of 1949.

It is worth pointing out that all three of these composers’ most popular choral works were created at the midpoint of each of their lives, all receiving their first performances during the 1940s, with the Barber taking place during the birth year of our next featured composer. Stephen Paulus, who died in 2014 following a devastating stroke, created some of the most beautiful choral music of the second half of the 20th Century. His Little Elegy was actually written in 2010, setting a poem of Eleanor Wylie (1885-1928), and exhibits the tenderness and sensitive word-setting that is a feature of Paulus’s very best choral writing. Not shying away from wide vocal ranges and dynamic contrasts, the piece maintains an intimacy that gives the impression that the listener is in a tender conversation from start to finish. The Road Home, written for the Dale Warland Singers, is based on a simple melody from The Southern Harmony Songbook (1835) and sets a text of frequent collaborator, Michael Dennis Browne.

Morten Lauridsen rose to international fame with his 1994 setting of O Magnum Mysterium, a piece which has become a staple of Christmas choral performances across the globe. Lauridsen’s thoughtful, carefully written, and evocative music earned him the label of “American Choral Master” by the National Endowment For The Arts in 2006. His musical style, as well as his teaching at the University of Southern California, has influenced a generation of American choral composers, as well as choral directors who have fallen under his spell. Nocturnes consists of three mixed chorus pieces, two with piano accompaniment, set to poems of Rilke, Neruda, and Agee. These three related works bask in the glory not only of Lauridsen's choral writing but also in the use of three languages within the set.

I only became aware of Randall Thompson’s piece Fare Well in the last couple of years and, as I played it through to myself, I was struck by the understated beauty and simplicity that Thompson creates. It was written in 1973 for the combined choruses of Calhoun, Kennedy and Mepham High Schools, in Merrick, New York. There is a poignancy to the piece that is reminiscent of Alleluia. However, there is also a realness to it – less of heaven, more of earth – that differentiates it from the piece that begins this program. It allows more space for the listener to reflect on the beauty of both text and music and is, in my opinion, an example of the best American Choral Music. There is something about it that tastes of America. It feels as though it gave birth to much of the American Choral Music that has followed it. Again, in my opinion, it is a better piece of music than Alleluia and, for whatever reason, it has never achieved the same level of recognition. This, after all, is the conundrum that has been around for centuries. A certain piece of music by a certain composer becomes popular and that composer is forever identified with it, while other – maybe better – works lie dormant. In this time of technological advancement, increased communications, media-driven bias, and all of the 21st Century norms, it will be fascinating to see the way in which creative landscapes will change and develop over the next one hundred years.

"This Little Babe"

My parents, immigrants fleeing the onset of World War II, came to the United States with their young family as refugees in 1940 -the year I was born. They were grateful and proud to be welcomed in America. As assimilated German Jews, their religion was German art and culture, mainly music. Christmas was celebrated in the German style, with candles (lit !) on the tree, and much music. Beginning with the First Sunday of Advent and daily in the week before Christmas, we gathered around the piano with my father atthe keyboard to sing traditional carols from the book by Henri Van Loon and Grace Castagnetti.

by Susanne Potts

My parents, immigrants fleeing the onset of World War II, came to the United States with their young family as refugees in 1940 -the year I was born. They were grateful and proud to be welcomed in America. As assimilated German Jews, their religion was German art and culture, mainly music. Christmas was celebrated in the German style, with candles (lit !) on the tree, and much music. Beginning with the First Sunday of Advent and daily in the week before Christmas, we gathered around the piano with my father atthe keyboard to sing traditional carols from the book by Henri Van Loon and Grace Castagnetti.

Someone had given us a vinyl set of recordings of Benjamin Britten’s A Ceremony of Carols, and my father - and all of us- became enormous and lifelong fans of Britten. I am so grateful that Donald Teeters shared that enthusiasm. Cecilia repeated that song cycle frequently, as well as many other of Britten's masterpieces.

Of all the carols, in their origins and variety, I am most deeply moved by Britten’s setting of Southwell’s text, 'This LittleBabe'. The image of the 'silly tender babe' shivering on a haystack, the infant Messiah clothed in rags “in freezing winter night”, is uniquely poignant.

For me, the story of the “freezing winter night” brings to mind not only the small babe in the manger, not long before his parents will have to flee Herod, but also my own parents flight from Germany and Hitler, and the current refugees fleeing Assad and the conflict and terror in Syria. Britten wrote A Ceremony of Carols as he returned to England in the midst of World War II. He had fled England at the start of the war, but felt he needed to return. It was a dangerous journey through a U-boat and submarine infested Atlantic. He had decided he needed to be back home. It is a gift for me to share this work and these memories with Barbara Bruns and Nicholas White and our audience.

CONNECTING WITH MYSTERY THROUGH MUSIC

BY NICHOLAS WHITE

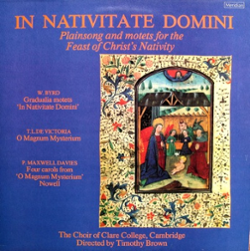

ust over thirty years ago, in September of 1985, I was awarded the organ scholarship to Clare College, Cambridge, which would result in my spending three years as an undergraduate at Cambridge University from 1986 to1989. The transformative experiences I gained in that position are too many to recount. However, one of the moments that stays with me from my audition and interview was when Tim Brown, the director of music at Clare, presented me with the choir’s latest recording. It was an LP of music by William Byrd, T. L. da Victoria, and Sir Peter Maxwell Davies entitled In Nativitate Domini. I remember being intrigued by the repertoire on the disc and noticed how well the two different compositional periods complemented each other.

Whether consciously or subconsciously, I followed this model when I formed Tiffany Consort in New York City. We would program concerts with music by composers of the same nationality who lived several centuries apart: Thomas Tallis and Michael Tippett, William Byrd and Benjamin Britten, Guillaume Machaut and Francis Poulenc, John Taverner and John Tavener, and so on. For this season’s Boston Cecilia December concert, I will pair the composers William Byrd and Francis Poulenc. I am returning to the William Byrd motets from his Gradualia II, which I heard on the Clare Choir recording thirty years ago. This time, the Byrd motets will alternate with Poulenc’s well-loved Quatre Motets pour le temps de Noël. Personally, I enjoy the ebb and flow this creates with regard to elements of texture, tonality and mood, as well as the more predictably contrasting—even jarring—harmonic and stylistic language of the two composers.

Also on the program is Edward Naylor’s Vox Dicentis. Naylor was organist of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and he wrote this sumptuous piece of choral music in 1911 for the choir of King’s College, Cambridge. My first memory of this piece was a performance by Clare Choir in Trinity College Chapel, Cambridge! With carols arranged and composed by two great musicians associated with Cambridge, Sir David Willcocks (King’s College), who died last month, and John Rutter (Clare College) who celebrated his 70th birthday last month, this concert could quite appropriately be titled The Cambridge Connection! However, there is more to the program than these offerings, including The Brookline Connection.

Last year, Charlie Evett, longtime member of Cecilia, commissioned me to compose music for two of his father’s poems. David Evett was deeply involved in the life of All Saints Church in Brookline, where he also sang in the choir. Charlie will write more in the next blog in this series regarding his father’s life and poetry, but I am pleased to announce that the December concerts will include first performances of both God’s Dream and His Unresisting Love, the latter being the text from which this concert takes its title. Both pieces are written for unaccompanied chorus.

This program brings together many styles and musical moods, and I hope that it does so in a way that will take the listener on a journey. Each of the texts exhibits elements of mystery, questioning, insecurity, wonder, doubt, and joy. Some of the music will be instantly appealing. Some will require further listening. My hope is that the program as a whole will capture the feelings that can only be achieved through the great mystery of musical expression.

HIS UNRESISTING LOVE: MUSIC FOR CHRISTMAS

Puer natus est nobis – William Byrd

O magnum mysterium – Francis Poulenc

Dies sanctificatus – William Byrd

Quem vidistis pastores dicite – Francis Poulenc

Tui sunt coeli – William Byrd

Videntes stellam – Francis Poulenc

O magnum mysterium: Beata Virgo – William Byrd

Hodie Christus natus est – Francis Poulenc

Hark! The Herald Angels Sing – Piae Cantiones, arr. D. Willcocks

His Unresisting Love – Nicholas White (world premiere)

God’s Dream – Nicholas White (world premiere)

Vox Dicentis: Clama– Edward Woodall Naylor

Good King Wenceslas – Piae Cantiones, arr. D. Willcocks

Sans Day Carol - Traditional arr., J. Rutter

What Sweeter Music - John Rutter

The Cherry Tree Carol – Nicholas White (world premiere)

You can listen to the 1985 Clare College Choir recording of the William Byrd motets here.

THE BRAHMS REQUIEM AS CHAMBER MUSIC

BY NICHOLAS WHITE

The German Requiem (Ein Deutsches Requiem) by Johannes Brahms is one of the most important works this composer produced. The opening three movements were first performed in Vienna during December 1867, and movements 1-3, 6 and 7 were performed in Bremen on Good Friday 1868. The first performance of the entire work took place at the Leipzig Gewandhaus on February 18th, 1869. Since then, the German Requiem has been one of the most frequently performed of all works in the oratorio repertoire. The compilation of Biblical texts on which it is based, all chosen by the composer, reflects a “sense of religiosity common to all mankind,” characteristic of the spiritual thinking of the mid 19th century. Despite certain reminiscences of earlier settings of the Requiem, Brahms’s work was viewed from the outset – quite correctly – as being entirely novel in both conception and execution.

Although the Requiem is usually performed with full orchestra, Brahms also arranged the piece for four-hand piano accompaniment. The piano version of the piece was first performed at the home of Sir Henry Livingston in 1871. On April 11th, The Boston Cecilia will present this more intimate arrangement of the Requiem.

In 1868, before the first performance of the complete work, the full score, orchestral and choral parts, and the vocal score (with the complete voice parts and piano solo reduction of the accompaniment by the composer himself) were issued by the publisher Rieter-Biedermann. This publishing house, founded in 1849, had a close association with Brahms during the 1860s and early 1870s. The musical material of the German Requiem printed by Rieter-Biedermann was augmented by the composer’s piano duet arrangement. The piano version of the German Requiem represents more than a mere arrangement of the orchestral parts for piano duet. It is a reworking of the entire score, including the vocal parts, to form an autonomous keyboard composition; this sets the accompaniment for our concert apart from a normal piano reduction intended for rehearsal purposes. In his quest for a piano duet texture which sounds well and is wholly pianistic in character, the composer proceeded in a manner which approaches creative reworking and fresh shaping of existing musical material. This applies, for example, to the many doublings by which particular melodies are brought out. In our performance, in order to preserve the luminous, transparent nature of certain solo and choral lines which would not be doubled in the orchestral version, we have made judicious cuts to the piano duet accompaniment, thereby leaving the chorus or the soloists undoubled by the piano.

By making this arrangement of the German Requiem for piano duet, Brahms was following a practice which was widely current during the 19th and early 20th centuries, of publishing symphonic works in transcriptions of this kind. Before the existence of recordings, arrangements such as this offered the public the best opportunity to become familiar with the composition in its entirety. Undoubtedly piano duet arrangements of this kind also represent a particular and once-popular class of publication for domestic music-making.

A presentation of Brahms’s well-loved masterwork in a form that is less familiar to the ear, like this one with an alternative form of accompaniment, gives us a unique opportunity as performers. In effect, as a chorus, we are able to approach the voice parts with a new perspective. Performing the piece then takes on a feeling of chamber music: a more direct, and in some cases more subtle, form of musical communication. There is a re-imagined clarity to the choral writing which, in combination with a truly pianistic accompaniment, presents the piece to the listener in a whole new way. Brahms’s masterpiece remains intact. The communication of it becomes fresh and newly invigorated.

Adapted, with additions, from Wolfgang Hochstein’s 1989 foreword to the Carus Edition.

Note: Paul Max Tipton, the baritone soloist for Cecilia’s April 11th performance, recently recorded this piano version of the Requiem for Seraphic Fire. (Listen - Clip 1) (Listen - Clip 2)

SIR JOHN TAVENER (1944-2013)

BY DEBORAH GREENMAN

When Sir John Tavener died almost exactly a year ago in November of 2013, the London Evening Standard headline read, “John Tavener: Farewell to Classical Music’s Cult Hero.” Probably the only classical composer to have been promoted by the Beatles, he was indeed both a brilliant classical composer and something of a cult hero. Ringo Starr and John Lennon were impressed by his cantata The Whale, and in 1970 it was released on their Apple label. The cantata’s text is the story of Jonah and includes instructions for snorting and yawning sounds by the chorus, to create the effect of whale sounds. Tavener achieved fame, fortune and a connection to the British royal family when his Song for Athene, a song composed after the death of a young Greek girl who was a family friend, was played at the funeral of Princess Diana. He was made a knight in 2000 just a few years later. His work ranged ever more widely. He composed Veil of the Temple in 2003 as an all night vigil. It was scored for four choirs, several orchestras and soloists, and lasted seven full hours. His Prayer of the Heart was written and performed for pop performer Björk, and in 2007, he wrote a piece called The Beautiful Names, the text of which is the 99 names of God in the Muslim tradition.

The composer had been captivated by music from the age of three and eschewed formal theory teaching for improvisation. Tavener was a man of contrasts, simultaneously fascinated with the intensity and asceticism of the Russian and Greek Orthodox traditions, yet flamboyantly dressed and delighting in good food and fast cars. A journalist once described him as “a mystic who drives a Rolls Royce.” Devoted – and even perhaps disturbingly attached – to his charismatic mother, he was not able to sustain a relationship with a woman and have a family until after his mother died when he was close to 50 years old. His most important collaborator was a mother figure, a Russian Orthodox nun named Mother Thekla. From the 1980s on, she either wrote or adapted nearly all of his texts until late in his life when – almost certainly as the result of tension between his wife Maryanna and Mother Thekla – he broke off their partnership.

John Tavener was surrounded by music as a child. Although his grandfather had a building business which his father later ran, father, grandfather, and many other family members played musical instruments. Tavener had perfect pitch and began improvising when he was three years old. In his book The Music of Silence A Composer’s Testament, a series of reflections and responses to interviews by his friend and editor Brian Keeble, Tavener wrote:

“But by far the most powerful musical experience I had at this time was hearing Stravinsky’s Canticum Sacrum. I heard the first broadcast performance from St Mark’s, Venice, when I was twelve years old. That completely overwhelmed me and made me really want to compose. For two or three years after it, I was imitating the sounds I’d heard.”

Perhaps beginning with Stravinsky and then enhanced by his relationship with Mother Thekla, Tavener would become more and more at home in the Russian Orthodox Church. His compositions are striking for their focus on text. He has a message, a spiritual message, to impart. He felt at home in the Orthodox Church because it was about immersion in the spiritual rather than an intellectual analysis of it. In his postlude to Tavener’s book, Keeble wrote, “Tavener’s belief that music is a way to ultimate truths capable of being integrated into life’s every moment necessarily hangs upon a religious and metaphysical vision of reality.”

In later life, Tavener was increasingly interested in Eastern religions and their unique tones. For some time, he had had little patience for music without a message, “frivolous music without the purpose of spiritual enrichment.” Tavener appreciated the way that music was woven into the fabric of both spiritual and everyday life in eastern culture. In an interview with the New York Times in 2000, Tavener said, “I listened to Indian music, Persian music, all music from the Middle East. I listened to American Indian music. I listened to any music that was based on traditional ideas. That’s when I started to question what on earth happened to this Western civilization and why the sacred seems to have been pushed out gradually by the domination of the ego.”

However, while recovering from cardiac surgery in 1991, Tavener listened again to Beethoven’s Late Quartets, and he began to return to the work of other modern composers as well. Although in his book, Tavener does not dwell on the impact of his medical problems on his spiritual life, it is hard not to see it as significant. He knew that he and his brother likely had Marfan’s syndrome, a connective tissue disorder that caused both his long-limbed body type and heart abnormalities. He had a stroke in 1980 when he was only 36 years old, and while recuperating read the introduction to The Life of St Mary by Mother Thekla that began his long and fruitful collaboration with her. About ten years after the stroke, he had cardiac surgery. He told Ivan Hewett, a reporter for the Telegraph in what would become his last interview, “my consultant keeps telling me sudden death could come at any moment.”

In The Music of Silence, Keeble asks Tavener what “state of being and what expectations would you like listeners to bring to a performance of your music?” Tavener replies, “First of all, I do not say ‘Do this, do that, Listen to this, Look out for that.’ That is the way of Western classical music. Rather I would say: here is something that is before all ages coming to birth – something new – something already known. But it is not what I have done that is important, rather the spirit that has animated it. Close the mind and open the heart. Expect nothing and you may receive ‘something.’”

Opening the heart seems an apt description of the way one might receive a performance of his song “The Lamb.” Tavener composed this utterly simple song in one day in 1982 for his then three-year-old nephew Simon. In The Music of Silence, Tavener writes “The Lamb’ came to me spontaneously and complete. I read Blake’s poem ‘The Lamb’ from the Songs of Innocence and as soon as I read it, the music was there…. Also, symbolism in the use of chords appears in The Lamb – there’s a joy/sorrow chord in it (Tavener refers here to the chord A-C-G-B) , on the word ‘lamb’ , which I was to use many times later.” For Cecilia’s Music Director, Nicholas White, hearing the second ever performance of this piece at age 15 was compelling: he was hearing something “radically different from any other carol” he’d heard before.

At our Christmas concerts on December 5th and December 7th, The Boston Cecilia will

perform “The Lamb” as well as a less-known set of pieces, Ex Maria Virgine. This latter cycle sets texts united by their focus on the person of Mary, Mother of God. It was commissioned by the Clare College Choir, completed on Christmas Day 2005, and “dedicated to HRH, The Prince of Wales and HRH The Duchess of Cornwall in joyful celebration of their marriage.”

It is hard to consider the constant refrain of homage to the mother Mary without thinking of Tavener’s powerful attachment to his own mother and his sense that she was crucial to his development as a composer. Tavener wrote about his piece: “I have set both familiar and less well known elements and linked them with an expanding and contracting phrase Ex Maria Virgine. This refers to Mary, Mother of God, and should be sung with great radiance and femininity.” The cycle uses the words of conventional English carols like “Ding! Dong! merrily on high” and texts from Greek and Islamic sources in a piece that challenges the listener. There is at once a sense of disconnection; is this medieval England or ancient Byzantium? Is that Latin or Aramaic? and then unity. Somehow the dissonant and melodic sections, the different languages, the angry words about the “The Empress of Hell” and the “lulla lulla” of the lullaby to rock the infant Jesu, all come together, united by the repetition at the end of each of the ten sections with the “expanding and contracting” phrase Ex Maria Virgine.

Perhaps in the later years of his life, some of the conflicts within this compelling, and passionate composer were also coming together. He had held onto his early fascination with Russian tradition, explored eastern religious and mystical tradition, focused on sacred texts and eschewed much of modern music, but he returned to Beethoven, Handel and others, and in his very last years set sonnets of Shakespeare to music. His funeral was in the Anglican Cathedral of Winchester but presided over by a senior Orthodox bishop.

On December 5th and December 7th, The Boston Cecilia will excitedly undertake the complexity of the brilliant and enigmatic John Tavener as we celebrate both his legacy and the Christmas season.

SWEET WAS THE SONG: MUSIC FOR CHRISTMAS

BY NICHOLAS WHITE

In 1982, when I was 15 years old, I first heard The Lamb by John Tavener. This second-ever performance of the carol was included in the Christmas Eve radio broadcast of Nine Lessons and Carols, live from King’s College, Cambridge. A much smaller audience had heard the very first performance of this newly-composed work at Winchester Cathedral two days earlier. I remember feeling that I had just experienced something radically different from any other carol I had heard before. The truth was that several million listeners across the world had just had the same experience, and the reputation of the composer, in the space of three minutes, had been propelled to a whole new level of renown. The music was stark, yet gentle; dissonant, yet comforting; simple, yet haunting. I think I made my decision shortly after that to pursue an organ scholarship at Cambridge University, which had me living, literally, in the shadow of King’s College Chapel for the three years of my undergraduate career. As it happens, I had followed in the footsteps of one of Tavener’s school friends and fellow composers, John Rutter, who had studied music at Clare College twenty years before me.

When John Tavener died, just a little over a year ago, I began thinking of how we might pay tribute to him with The Boston Cecilia. I had been aware of a series of commissions that Tavener had written around 2005, which resulted in a sequence of carols entitled Ex Maria Virgine. This sequence had been recorded by Tim Brown and the Choir of Clare College, Cambridge in 2008. As I listened to the recording, made in the grand surroundings of the Chapel of St. John’s College, Cambridge, I decided that it would provide the ideal challenge for The Boston Cecilia and a great way of celebrating the life of John Tavener at our December concerts. The luxurious acoustics of The Church of the Advent and All Saints, Brookline, along with their fine organs, would create an ideal vehicle for this eccentric music.

Also on my mind at this time was Richard Rodney Bennett, whose music had captured my interest at a very early age when I learned several of his compositions for piano. Later on in life, we ended up as neighbors on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and I was fortunate in getting to know Richard, talking about his film scores, and discussing choral music, occasionally over dinner at a local restaurant. In the year 2000 I had conducted the New York premiere of his large-scale work for choir and organ, The Glory and the Dream, and the organist for the performance was none other than Barbara Bruns, for whom Richard had the highest praise. Richard died on Christmas Eve of 2012. As I had long been familiar with his Christmas carols, I instantly thought that these would provide a perfect complement to Tavener’s works, so I went about assembling the program that will be performed by The Boston Cecilia on December 5th and 7th, 2014.

According to Tavener, The Lamb was written in an afternoon and is built on a simple melodic idea and its inversion. Tavener’s tempo direction for the piece is explicit and simple: “With extreme tenderness – flexible – always guided by the words.” For those of us who are devoted to the art of choral singing, there is surely no better way of conducting ourselves.

CECILIA: WE'LL E READY FOR BACH'S B MINOR MASS

BY NICHOLAS WHITE

“If we’re not ready now, we never will be…!”

The quotation above was overheard at a church music conference several years ago, soon before a late-afternoon performance of Bach’s B Minor Mass sandwiched between workshops and plenary sessions and a boozy evening boat cruise. Ideal circumstances for a cutting edge, historically-informed performance of this two-hour masterwork, with the finest-period instrument players and a 26-voice professional choir? Maybe not! However, as the conductor responded to the concerned delegate who wondered why the performers were not busily rehearsing in the hours before the concert, “If we’re not ready now, we never will be!”

He was right, of course. Not only had the musicians been meticulously prepared, again, for this latest performance of the great work. In the director’s seemingly flippant comment was the truth that any performer must grasp when about to embark on the life-changing experience of this piece. The nitty-gritty detailed rehearsal needs to be accomplished far ahead and the big picture embraced well before concert week. Stamina, fortitude, the ability to respond in the moment, and a spark of spontaneity are among many elements that constitute a successful performance of Bach’s Mass in B Minor, a performance that will engage the audience and harness the emotions of all those present.

That’s why I’m glad that the dress rehearsal for the March 21st performance by The Boston Cecilia is on Wednesday, March 19th, two days prior, giving a full day for reflection before the concert itself. In every way, the final rehearsal takes on the mantle of a performance. It must do so if we are to stand any chance of being ready. That one remaining part of the equation – the audience – will then play its own role in the success of the actual concert.

That’s why I’m glad that the performance—along with Bach’s 329th birthday—comes on a Friday evening, at the end of a long work week, when spirits are sagging, the commute to Jordan Hall has been challenging, the weather is unpredictable, and energy needs to be summoned from somewhere. This is when performers and audience members can come together, inspired by each other, to create moments of magic that transcend the real world. Yet this masterpiece is packed with humanity, almost unachievable by mere mortals, and can feed from those challenges that we, as humans, face on a daily basis.

That’s why I’m glad that Cecilia had the foresight to reserve Jordan Hall for this occasion, even before I had been hired as music director! What a gift for all of us to end the 138th season of this great organization with a performance of Bach’s masterpiece. It is very real, very relevant, and very exciting.

We will be ready! Won’t you join us?

I WONDER... WHAT IS A CAROL?

BY NICHOLAS WHITE

A good Christmas carol needs to have a good tune. Whether or not one subscribes to this concept, the dictionary definition of the word carol suggests “a song of joy or mirth, a popular song or ballad.” For me, the most memorable expressions of joy around the holiday time come from the most simply tuneful, rhythmically playful and sublime musical offerings. In our December program, we will offer a broad palette of carols that, I feel, fit that description.

Some of the most effective programming choices seem to happen subconsciously, just as much as they follow lengthy, serious consideration. This year’s program, entitled “No Small Wonder” is no exception. In assembling this program of mostly 20th Century works from England, Wales and America, it strikes me again that beautiful choral music transcends national boundaries and language. Well over half of the program actually uses a mixture of English and Latin within the same composition, and these macaronic offerings underscore the power of melody and song in the effective communication of the Christmas message.

John Jacob Niles’ haunting melody to I Wonder As I Wander is given elegant treatment by John Rutter as the program softly begins, with undulating harmonic support from the choir. This is followed by the crisp, clean rhythms of Samuel Scheidt’s Puer Natus In Bethlehem, the buoyant melody of the soloist reflecting the excitement of the message, and provoking an exuberant choral response. Robert Lucas Pearsall’s radiant arrangement of In Dulci Jubilo has become a favorite of choirs across the world. Pearsall translated the German words into his own English version, and maintained the original alternation with the Latin phrases, ending with an extended development of the music for the words “O that we were there.”

Carols are intended to be sung by everyone. Following the short organ solo, one of Bach’s fantasia-style chorale preludes on the In Dulci Jubilo tune, the audience will get a chance to join in the singing. The First Nowell is from 18th-century Cornwall, arranged by David Willcocks in various harmonizations for the choral forces. The audience is invited to join in the singing of the refrain throughout.

Ave Rex by Welshman William Mathias was first performed in December 1969 by the Cardiff Polyphonic Choir in Llandaff Cathedral. It was commissioned by the choir and is a sequence of three contrasting anonymous medieval carols framed by a dramatic setting of the invocation Ave Rex itself. The three carols are a high-spirited Alleluya; an introspective setting of There is no Rose and finally the cheery and joyful Sir Christèmas. The work concludes with a reprise of the sequence’s opening material.

The second half of the program begins with the work from which this concert takes its name. Paul Edwards wrote this lush, jazz-inspired setting of Paul Wigmore’s poem with its recurrent phrase “no small wonder” in 1983, and it has become much loved by choirs during the last three decades. The foundation of the organ provides a rich, warm bed of harmony for the simple melody. Indeed, it is the harmony that provides the greater part of the intrigue in this piece.

Peter Warlock (born Philip Heseltine) was a music critic and composer of some notoriety, his chosen pseudonym reflecting his interest in occult practices! The set moves from the simple, yet powerful, unison setting of Adam Lay Ybounden, through the poignant setting of Bruce Blunt’s poem Bethlehem Down with its earthy imagery, on to the gentle Balulalow and culminating in the riotous exuberance of Benedicamus Domino. These four of Warlock carols demonstrate a rich variety of textures that are undeniably from the pen of a master craftsman with a distinctive musical voice.

Distinctive musical voice is a quality that can certainly be applied to the French composer on the program tonight. While we are not featuring any delicate early French Noëls here, Barbara Bruns will play one of the most popular of Olivier Messiaen’s works for organ, the final movement from his nine-piece cycle La Nativité du Seigneur, known as Dieu parmi nous, or “god among us.” Messiaen’s unique harmonic language and virtuoso writing for the organ builds to a grand toccata that, with the thrusting descent of the pedal line, symbolizes God coming down from heaven.

John Goss was a professor of harmony at the Royal Academy of Music from 1827-1874, and was also organist of St. Paul’s Cathedral, London. His setting of Edward Caswall’s text has again been arranged by David Willcocks, inventively varying the combinations of voices. The audience is invited to join in the refrain of See amid the Winter’s Snow.

Richard Wayne Dirksen spent his entire career at Washington National Cathedral, where he was influential in many areas, most especially in musical leadership, creation and teaching. A Child My Choice was written quickly, in response to the need for some music to fill out the time on a live Christmas broadcast. Dirksen’s setting of Southwell’s words has subsequently become a favorite of choirs all over the United States. The simple, lilting 5/4 time and straightforward opening harmonies belie a depth of emotion that comes through in the middle of each verse. In short, this carol represents the very best example of simplicity reaching the listener in a profound way.

The final three pieces on the program are shining examples of the type of carol that any listeners would want to allow to simply wash over them as they sit within the walls of some gothic cathedral church, as the snow falls outside and the candlelight glimmers within, to usher in the holiday season is. Grayston Ives was a member of The King’s Singers, and subsequently Informator choristarum at Magdalen College, Oxford. Sweet Was The Song is an example of his lyrical style, written with a full understanding of vocal elegance, and reminiscent of Rutter’s earlier carol, What Sweeter Music. Benjamin Britten, whose 100th birthday we celebrate as I write these notes, is best known for his Ceremony of Carols. His elegant A Hymn to the Virgin, for double choir, composed in 1930 during an enforced spell in the infirmary at Gresham’s School when he was only sixteen years old, shows Britten’s mastery of compositional techniques and choral textures from a very young age. Another macaronic text, the solo quartet interjects Latin phrases in response to the choir’s lines of poetry in honor of the Lady, flower of everything.

We end with one of John Rutter’s earliest carols, for which he wrote both words and music. Published in 1967, The Nativity Carol alternates lines of heart-on-the-sleeve poignancy with a simple refrain of the Christmas message. Achieving everything that its predecessor, In The Bleak Midwinter by Harold Darke, achieves, Rutter’s carol has in its own way become a classic example of the sound of Christmas.

TAKE HIM EARTH FOR CHERISHING: 50 YEARS AFTER JFK

BY DEBORAH GREENMAN

On November 22, 1963, forty-six year old John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the nation's thirty-fifth President, was assassinated on a Friday afternoon in Dallas, Texas. The first music performed in his memory may well have been at Boston’s Symphony Hall. People who were at the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s Friday afternoon concert were given the shattering news by Erich Leinsdorf who then conducted an impromptu performance of the Funeral March from Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony.

And not long after Kennedy's death, British composer, Herbert Howells, was asked to write a piece for a joint Canadian-American Memorial Service. The piece, the motet Take Him Earth for Cherishing, was completed the following spring, and was first performed November 22, 1964—the first anniversary of Kennedy’s death—by the Choir of the Cathedral of St George from Kingston, Ontario. George N. Maybee conducted in Washington’s National Gallery. The concert featured commissioned works, not only by Howells, but also by a Canadian, Graham George, Professor of music at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario and an American, Leo Sowerby, the Director of the College of Church Musicians of Washington Cathedral. Graham George’s piece was set to Herrick’s text, “In God’s Command Ne’er Ask the Reason Why”; Sowerby’s was a setting of six verses of Psalm 119.

November 2013 will mark the 50th anniversary of President Kennedy’s death, so it seems fitting that Boston Cecilia, led by its new director Nicholas White, will perform the motet on November 2nd at All Saints Church. The November 2nd concert will also include three pieces by Charles Villiers Stanford, Howell’s first professor of composition; Stanford called Howells “My son in Music.”

At the time that Howells was asked to compose a piece in memoriam, he was well known as the composer of a choral symphony of death and transfiguration, Hymnus Paradisi, composed in memory of his beloved son Michael who died at age nine of polio. Howell’s anguish is vividly recorded in his diary with the words, ”One feels the futility of all the things one usually sets value on when one is faced with reality.” The title of the Hymnus comes from Prudentius, a fourth century scholar in the judiciary of Emperor Theodosius who wrote Hymnus Circa Exsequias Defuncti, translated by Helen Waddell as Hymn for the Burial of the Dead. (Much later it was suggested that Howells change the title to the more manageable Hymnus Paradisi.)

The first two lines of this poem—initially intended for the Hymnus itself —became the epigraph for the Hymnus. Those lines “Nunc suscipe, terra, favendum, gremioque hunc concipe molli,” Waddell translates as “Take him earth for cherishing, To thy tender breast receive him.” Nearly fifteen years after composing the Hymnus and thirty years after the death of his son, Howells would return to those lines for the motet in memory of Kennedy.

In a sleeve note to an Argo (RG 507) recording of the piece, Howells wrote:

“I was asked to compose an a cappella work for the commemoration (of Kennedy). The text was mine to choose, Biblical or other. Choice was settled when I recalled a poem by Prudentius (AD 348-413). I had already set it in its medieval Latin, years earlier, as a study for Hymnus Paradisi. But now I used none of that unpublished setting. Instead I turned to Helen Waddell’s faultless translation:

Take him, Earth, for cherishing,

To thy tender breast receive him.

Body of a man I bring thee,

Noble even in its ruin.

Here was the perfect text—the Prudentius ‘Hymnus Circa Exsequias Defuncti’. The motet is sung here as intended—wholly for unaccompanied voices. Formally it is roughly A-B-A; in texture variably 4- to 8-part. Tonality anchors (first and last) on B, but admits chromatic phases, as at:

Ashes that a man might measure

In the hollow of his hand.

Finally, a near-funeral match tethered again to B, but in the more consoling major mode.”

Howells composed Hymnus Paradisi as a way of working through the pain of his son’s early death. With Take Him Earth for Cherishing, he would return to the words of the Hymnus epigraph to bring consolation to an entire nation. Take Him Earth for Cherishing would then be performed at Howells’ own Memorial Service in St John’s College Chapel, Cambridge in May of 1983, nearly twenty years after it was first performed in memory of John Fitzgerald Kennedy.